Communication is the life-blood of an organisation. Dialogue needs to be honest: seeking objectivity, reducing bias and never covering up truths or views to make things ‘comfortable’. However, a habit of bad conversation stifles problem-solving, dampens enthusiasm and encourages the building of defensive routines.

From my own organisation and having worked with many schools, training providers and charities, it’s clear that the good communication begins with the leaders. As a leader there is always an enormous temptation to jump in and start giving advice without having really listened to the issue, without having sought enough perspectives, and without leaving room for others to grow their own solutions. The trouble is, however good your ideas, they come with a big shiny sign that say ‘the boss likes this, I should prioritise her/his thinking above my own’. What we want is a culture where great ideas and great thinking can take root, driven by everyone.

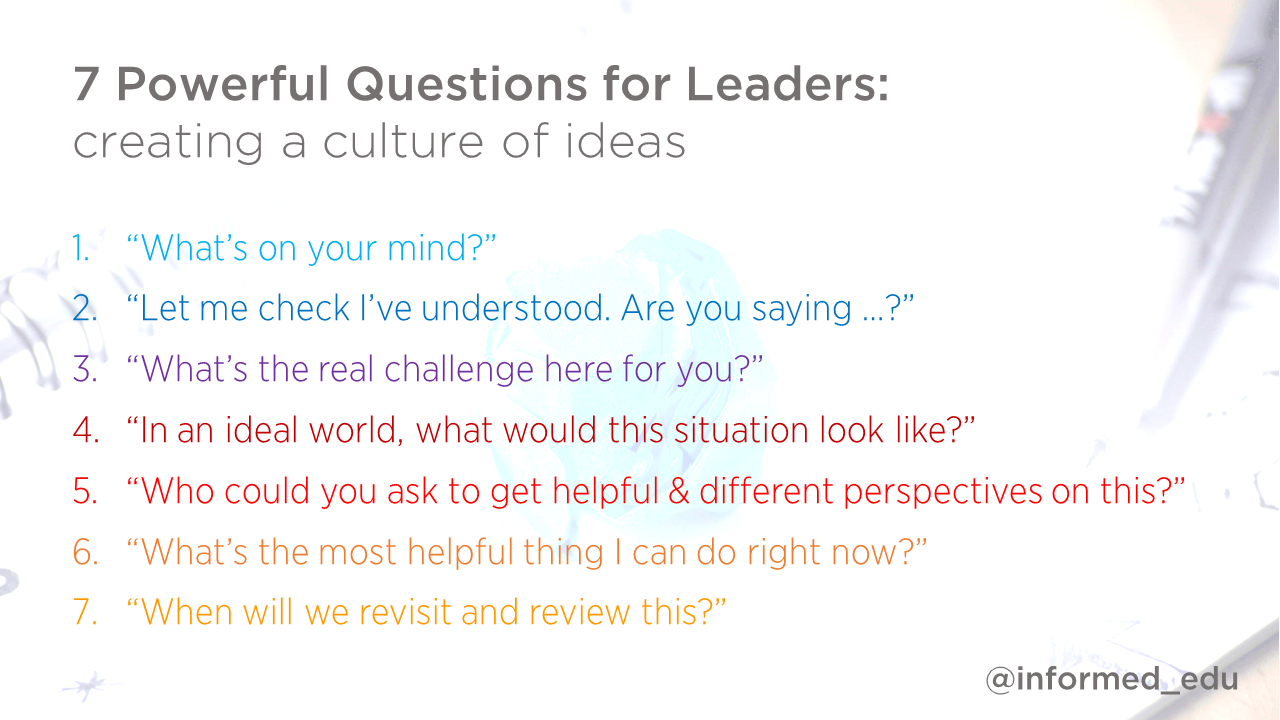

Here are 7 questions which I think can help.

1. “What’s on your mind?â€

This is a great way to open a conversation – it signals that you’re interested in what the other person is thinking, and that you’re open to hearing concerns. It puts the ball in the other person’s court; they get to name the priority and they have control over the agenda.

This question needs to be used together with question 2 which is…

2. “Let me check I’ve understood. Are you saying <re-phrase and summarise>?â€

It’s worth doing this check even if you’re reasonably certain you have understood. As you’re listening to what is being said you’re automatically reinterpreting it to your own view of the world. It’s useful to try and re-phrase/summarise and check that a) you’re on the right track and b) you haven’t missed something that’s important to the other person. Sometimes, when I listen to people, some elements of their dialogue spring out at me, but when I summarise the overall meaning I discover that I’ve distorted or obscured some of the key meaning that the other person intended. This technique demonstrates that your first priority is listening and understanding, not to jump in and take over control of the problem or situation.

A way of making questions 1 and 2 work together even better is to physically sit next to each other during the conversation, perhaps on two adjacent sides of a table, and sketch out ideas as the other person speaks. It could be a flow chart or a napkin sketch. It slows the process down, ensures you can repeatedly check that you’re on the same page, and allows the other person to see a map of what they’re saying and refer back to it later.

I’m grateful to Oliver Caviglioli for introducing me to this whole area of sketching, especially napkin sketching. It certainly takes some practice and it’s not always the right solution, but I have found it useful.

3. “What’s the real challenge here for you?â€

This is a lovely question which I recently read in The coaching habit: Say less, Ask more & Change the way you lead forever†(Michael Bungay Stanier). It’s helpful when someone has given you a laundry list of issues or concerns, or where someone has gone round in circles, or is being fuzzy. It forces the other person to search for the nugget that is really important, that matters most. As Stanier says, the word real “implies that there are a number of challenges and to choose from, and you have to find the one that matters most. Phrased like this, the question will always slow people down and make them think more deeply.†The words ‘for you’, are “what pin the question to the person you’re talking to. It keeps the question personal and makes the person you’re talking to wrestle with her struggle and what she needs to figure outâ€. [quotes from the book, Chapter 3]

4. “It sounds like you’re frustrated/disappointed/angry with X. This suggests that you have a vision in your head of what X should ideally be like, and it’s falling short. Could you describe that vision/ideal?â€

This question has led to a few breakthrough moments for me, not only with other people but also even challenging myself to answer it. I was inspired to try this approach after a conversation with Tony Nicholls who inspired me to read about appreciative inquiry, an approach/philosophy of change and improvement that invites people to focus on the positive, not the negative.

This question draws on the ‘dream’ element of appreciative inquiry which is about articulating potential. It allows people to start describing and fleshing out an alternative reality. I have found that people often drift back quickly to describing the deficits – it takes quite a lot of gentle steering to get the other person to stay on ‘positive’ first, while not making them feel you’re ignoring the facts and emotions around the problems – e.g. “I can see that you find that frustrating. I’m keen to understand your ideal so that I can understand why the current situation is falling short.â€

It allows them to imagine some light at the end of the tunnel and flip a negative conversation into one with more potential. Once the desired future is clear, it’s much easier to see the path to get there.

5. “Who could you ask to get helpful and different perspectives on this?â€

This question serves multiple purposes. Firstly, as a manager, your instinct is to give your perspective and try and solve the problem. This question interrupts that instinct and helps the other person look elsewhere, using their own resourcefulness to do so. Secondly, it ‘zooms out’, reminding both of you that everyone sees the world from their own point of view, that everyone will be missing something, and that multiple perspectives are better than any one.

It’s not necessarily an easy question. If someone is feeling stressed and emotional then it’s hard to ‘zoom out’. An invitation to do so may even sound like a criticism. It may be the right thing to do to simply ‘park the conversation’ and say “it’s good to understand your point of view on this. Can we take a break to allow us both to reflect on this a bit?†You can then come together when the tension is lower, summarise where you were and start the process of ‘zooming out’.

Once you do start thinking of people, it’s worth teasing out “why do you think that person’s perspective might be helpful and different?†as this continues the process of helping the other person imagine themselves in other people’s shoes.

6. “What’s the most helpful thing I can do right now?â€

It may be that the other person simply wishes to make you aware of something. It may be they want a specific piece of guidance. Maybe they want some feedback. It puts the ball in the other person’s court to say what you should do. It also stops you from going into ‘telling’ mode by default.

You have probably already helped by simply getting the other person to clearly articulate an issue and what the solution could look like, as well as sources of perspective and expertise. You might have (hopefully) sparked a sense of curiosity and drive to solve the problem.

Even if you’re asked for an opinion you might sometimes say “let’s see what you come up with first as it might be better than any idea I come up withâ€, or “I could come up with some ideas but I’d rather hear yours first.†Note that it’s worth avoiding signalling that you have ideas that you’re simply hiding or else you could just encourage a game of ‘guess what’s in my boss’s head’.

7. “When will we revisit and review this?â€

Toward the end of a conversation you may both feel some relief that some difficult ground has been covered, or excitement that a seed has been sown. However, part of the reason that progress has been made is because you have a) paid attention to it, b) given permission for thinking and honesty and c) made it clear that the other person has ownership. Over time, the other person may see your attention fade, they may start doubting if they are still allowed to be creative and honest, and they may start interpreting things you’re doing and saying (outside of the meeting) as signalling that you’re taking back ownership.

I’ve learned this the hard way, with colleagues feeling I started some creative thinking and then interpreting later actions (sometimes rightly, sometimes wrongly) as implicitly ‘dousing the flames’. It’s important to review and revisit ideas together, if only to continue to show that you’re not just about to jump onto the field of play uninvited – nor end the game early and start a new one – but that you are still very interested and enthusiastic. You may have planted a seed and started an initiative because it’s something you’re excited about. When you come back to it, you may now be excited about something very different. However, by reconnecting, showing interest and attention, and encouraging energy and curiosity, you can stay engaged and seek to maintain growth.

Conclusion

I’ve come to learn that I’m often at my happiest when I’m constantly exploring new ideas and sharing things that excited me. However, I’ve also learned the hard way that a tendency to be slow to listen but be quick to share my ideas, suggestions and latest enthusiasm has a toxic effect that encourages others to feel their own ideas aren’t valued and that they are not being heard.

I’m fascinated by the 7 questions above as a way of learning how to keep turning this dangerous habit on its head. I hope they’re of some use to you and I’d warmly invite you to share with me any critique, ideas or questions.

Some further reading

I’ve been enjoying these books recently – they’ve helped to spark some of this thinking.

Note: thanks to Dame Alison Peacock whose wonderful mantra ‘a culture of ideas’ continues to guide so much of my thinking.